![]()

LINER NOTES DI SEAN

WILENTZ DA "THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 6: CONCERT AT PHILARMONIC HALL"

di Sean Wilentz

traduzione di Michele Murino

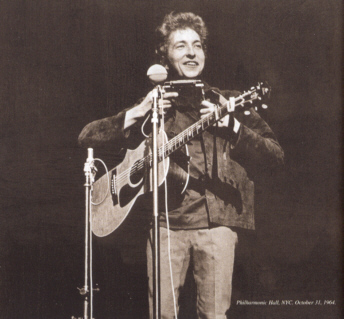

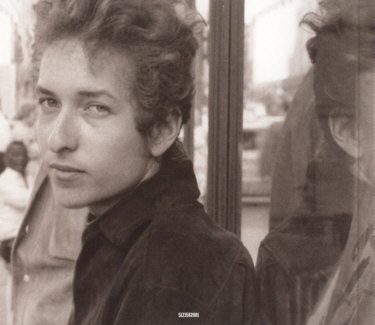

Nella notte di Halloween del 1964, un Bob Dylan ventitreenne affascinò un

pubblico adorante alla Philarmonic Hall di New York. Rilassato e di buon

umore, cantò diciassette canzoni, tre delle quali con la sua ospite Joan

Baez, più un bis. Molte di quelle canzoni, sebbene fossero vecchie di

appena due anni, erano così conosciute che il pubblico sapeva a memoria

ogni singola parola. Altre canzoni erano nuovissime e sconcertanti. Dylan

diede il cuore nell'esecuzione di queste nuove composizioni, come del

resto fece anche per quelle vecchie, ma solo dopo un'introduzione alquanto

ironica.

Questa si chiama "Una sacrilega ninna nanna in fa minore", annunciò prima

di iniziare la seconda esibizione pubblica di sempre di "Gates of Eden".

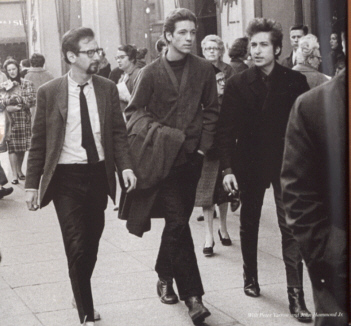

Egli era il centro dell'attrazione del movimento hip, quando gli hip

ancora indossavano pantaloni attillati e lucenti stivali di pelle

scamosciata marrone (come ricordo che egli indossava quella sera).

Tuttavia l'hip si stava trasformando proprio sul palcoscenico. Dylan si

stava già spingendo più lontano, ben al di là di quanto potessero fare

anche i più accorti newyorkesi presenti in sala, e stava cantando a

proposito di quel che stava trovando lungo questo suo nuovo cammino. Il

concerto fu in parte la summa dei suoi lavori passati ed in parte la

chiamata ad una esplosione di novità per la quale nessuno di noi, e

nemmeno lo stesso Dylan, era pienamente preparato.

"Visto che Dickens, Dostoevsky e Woody Guthrie raccontavano le loro storie

molto meglio di quanto potessi mai fare io, allora decisi di seguire le

mie idee."

- Bob Dylan, 1963.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Il mondo sembrava sempre più diviso durante le settimane che precedettero

il concerto. Il trauma dell'assassinio di John F. Kennedy, meno di un anno

prima, era diminuito appena. Nel corso dell'estate gli omicidi degli

attivisti per i Diritti Civili James Chaney, Andrew Goodman e Michael

Schwerner avevano creato nuovi traumi. Il Presidente Lyndon Johnson riuscì

a far passare al Congresso un progetto di legge per i Diritti Civili nel

luglio del 1964; all'inizio dell'autunno sembrò che egli avrebbe

facilmente sbaragliato l'arciconservatore Barry Goldwater nelle prossime

elezioni. Ma in agosto Johnson ricevette un assegno in bianco da parte del

Congresso per aumentare il coinvolgimento Americano nel conflitto

vietnamita. In un solo giorno a metà ottobre, il leader sovietico Nikita

Krushchev fu sconfitto e la Cina Comunista fece esplodere la sua prima

bomba atomica. La fase di speranza di un decennio terminò velocemente e si

andò profilando una fase più terrorizzante.

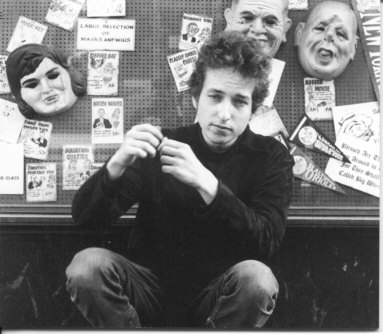

Anche lo stile di Dylan e la sua arte stavano cambiando, con una rapidità

estremamente accelerata e sconcertante per quei tempi. Nel dicembre del

1963 Dylan aveva offeso un pubblico di sinistra a New York pronunciando un

discorso a ruota libera, mentre accettava il Tom Paine Award, con commenti

maldestramente pronunciati ed improvvisati a proposito dell'ipocrisia,

dell'alienazione giovanile, e di come egli vedesse un po' di se stesso in

Lee Harvey Oswald, l'assassino di Kennedy.

Proclamato dagli uomini di sinistra come la nuova incarnazione di Woody

Guthrie, come un nuovo eroe politico, Dylan aveva dato l'impressione di

essere a disagio, compiaciuto per il fatto di essere premiato ma

malvolentieri accettando il pesante fardello che tutte quelle persone

anziane, per le proprie personali ragioni, volevano mettergli addosso; e

così, in maniera ambivalente e facilmente frainteso, egli respinse

indietro il manto. Il cantante offese persino più persone l'estate

successiva con la pubblicazione di Another Side of Bob Dylan - un album

nel quale non c'erano più i punti di vista morali che avevano

caratterizzato le sue prime canzoni di protesta e che al contrario

conteneva canzoni di libertà personale alquanto bizzarre e che parlavano

di amore ferito.

Sulla scia del rilevamento da parte dei Beatles della classifica alla

Radio Americana dei 40 dischi più venduti, alcuni membri del più vecchio

establishment folk scossero le proprie teste sgomenti nel vedere quello

che stava diventando il loro nuovo Woody Guthrie. Un commissario del

popolo folk, scrivendo sull'autorevole rivista Sing Out!, dimostrò sdegno

nei confronti del Dylan che stava abbandonando la politica e provò a

costringerlo a tornare in riga, ammonendolo di non trasformarsi in "un

Dylan differente da quello che noi conoscevamo." Egli non sapeva in realtà

che Dylan non stava semplicemente diventando diverso; egli stava anche

ascoltando i Beatles.

Dylan ha sempre ricordato quanto lo avessero ferito le critiche ad Another

Side, e quanto egli fosse stato orgoglioso quando Johnny Cash aveva

scritto una severa lettera a Sing Out! in sua difesa. (Dylan ha dichiarato

che ancora oggi conserva la sua copia della rivista con la lettera di

Johnny Cash.)

Ma all'epoca egli non tradì esternamente i propri sentimenti feriti e

continuò a scrivere e ad esibirsi nella sua nuova vena.

La grande maggioranza dei suoi fans, specialmente quelli più giovani,

sembrarono approvare. Al Newport Folk Festival in luglio, due settimane

prima che fosse pubblicato Another Side, egli suonò quasi interamente

nuovo materiale, insieme ad una canzone non ancora registrata che egli

presentò nella session di prova di quel pomeriggio con il titolo di "Hey

Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me." E il responso fu estatico. Dylan

era ancora la grande star della musica folk, un fenomeno come nessun

altro, non importava cosa egli cantasse.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Per molti dei lealisti, i cambiamenti nello stile di Dylan (a differenza

che nel resto del mondo) non erano considerati di disturbo. Nel bel mezzo

della invasione rock inglese, Dylan ancora rimaneva da solo lì sul palco,

e cantava e suonava con niente altro che la sua chitarra e la sua

armonica. Quando non era da solo, cantava, a Newport e da qualsiasi altra

parte, con Joan Baez, la cui presenza ed appoggio delle nuove canzoni di

Dylan attenuò il nostro personale cambiamento. In realtà la politica non

era sparita dalle canzoni di Dylan ma era soltanto diventata meno

caratterizzata da prediche e più strana, divertente, come nella saga del

gioco di parole "Motorpsycho Nitemare" su Another Side. Dylan aveva sempre

cantato in maniera intensa canzoni personali. Il suo primo e più

importante materiale politico spesso aveva riguardato storie con risvolti

umani come "The Lonesome of Hattie Carroll." E nel mezzo del

disorientamento della fine del 1963 e dell'inizio del 1964 chi poteva dire

che una svolta verso l'introspezione fosse fuori luogo?

I Beatles, con i loro strani accordi e con le loro gioiose armonie, erano

grandi, ma che cos'era "She Loves You" se paragonata alle immagini di

"Chimes of freedom"? Chi altri se non Dylan poteva essere talmente

intelligente e talmente abile da inserire nelle proprie canzoni allusioni

ai film di Fellini ed a Cassius Clay? Per i suoi fans forse egli si stava

evolvendo ma allo stesso modo anche noi ci stavamo evolvendo; ed il Bob

Dylan che adesso ascoltavamo e vedevamo sembrava fondamentalmente lo

stesso Bob Dylan che conoscevamo, solo migliore. A guardare indietro la

cosa oggi, probabilmente non avevamo che un piccolo indizio circa il luogo

verso il quale era diretto, rispetto a quello che aveva lo scrittore di

Sing Out!

Ma a quell'epoca, per quelli di noi che volevano essere quanto più vicino

possibile al filo del rasoio dell'avanguardia - o quanto più vicino

osassimo essere - Dylan non era in errore.

"I don't want to fake you out,

Take or shake or forsake you out,

I ain't lookin' for you to feel like me,

See like me or be like me"

- Bob Dylan, 1964.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

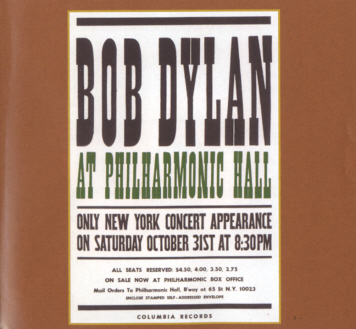

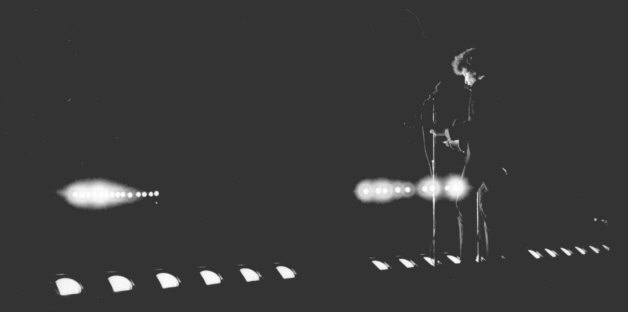

Il fatto che il management di Dylan scegliesse la Philarmonic Hall per il

più grande show newyorchese dell'anno per la sua star era la testimonianza

della sua capacità di attrattiva. Inaugurata solo due anni prima, la

Philarmonic Hall (attualmente Avery Fisher Hall) era con la sua grandeur

imperiale e la cattiva acustica, l'auditorio più prestigioso a Manhattan -

o per quel che importa nell'intero paese. Nel giro di due anni dall'uscita

del suo primo album i luoghi dei concerti di Dylan a New York erano

diventati sempre più importanti (e ulteriormente lo sarebbero diventati),

dalla Town Hall alla Carnegie Hall ed ora alla nuova scintillante casa di

Leonard Bernstein e della New York Philarmonic.

Quando il pubblico in attesa fluì dalla vecchia fermata della

metropolitana IRT dalle mattonelle a mosaico della 66ma strada e si era

andata stipando nel cavernoso e dorato teatro, probabilmente sembrò agli

abitanti dei quartieri alti (ed agli uscieri) come se si trattasse di una

bizzarra invasione di giovani hip beatnik.

Quasi ad assicurarsi che ci rendessimo conto di dove ci trovavamo, apparve

un uomo sul palco prima dell'inizio dello show per avvertirci che non

sarebbe stato possibile scattare fotografie o fumare. Poi, come Bernstein

che cammina a grandi passi verso il suo podio, Dylan camminò sul palco

uscendo dalle quinte senza alcun annuncio e fu una fanfara di applausi ad

annunciare di chi si trattava.

Egli iniziò il concerto, come abitualmente faceva, con The Times They Are

A-Changin'.

Eravamo tutti autoconsapevoli, sensibili e perspicaci, pronti ad assistere

ad uno show di Dylan come nessun altro, qualsiasi fosse il lusso che ci

circondava.

Due ore più tardi avremmo lasciato l'edificio e saremmo tornati verso la

metropolitana della IRT, ilari, divertiti, ma anche confusi ripensando ai

frammenti di versi che avevamo raccolto qua e là da quelle strane nuove

canzoni. Che cos'era quella strana "ninna nanna in fa minore"? Che cos'è,

nel nome di Dio, un "gabbiano profumato" (o forse aveva cantato "ragazza

del coprifuoco") (1)? Davvero Dylan aveva scritto una ballata basata sulla

"Darkness at Noon" di Arthur Koestler? Le melodie erano potenti; e quel

suono della canzone dell' "oscurità" (2) era stato sinistro e potente, ma

aveva mosso tutto così velocemente che la comprensione era stata

impossibile.

Lo show si era rivelato differente rispetto ad ogni altro show cui

avessimo mai assistito.

Grazie ad un eccellente nastro, presentato qui per la prima volta nella

sua interezza, è ora possibile apprezzare quel che accadde quella sera -

non solo in relazione a quel che Dylan cantò, ma anche in relazione a quel

che egli disse, ed all'incredibile rapporto che ebbe con il pubblico e che

si può chiaramente udire nel disco.

Lo show venne diviso in due parti con un intermezzo di quindici minuti. La

prima metà dello show fu dedicata alle novità affiancate da alcuni sguardi

all'indietro a dove Dylan era già stato. Le due vecchie canzoni più

prettamente politiche non erano mai state pubblicate su disco ma il

pubblico le conosceva bene e rispose entusiasticamente.

Nel maggio del 1963 Dylan avrebbe dovuto partecipare all'Ed Sullivan Show,

il programma di punta in televisione la domenica sera, dove Elvis Presley

aveva fatto tre apparizioni sette anni prima ed aveva accettato, nello

show conclusivo, di essere inquadrato solo dalla vita in su.

Il gruppo tradizionale irlandese dei Clancy Brothers e Tommy Makem erano

apparsi all'Ed Sullivan Show due volte, aumentando largamente il proprio

seguito di appassionati (avevano suonato alla Philarmonic Hall un anno

prima di Dylan).

I Limelighters, i Lettermen, i Belafonte Folk Singers ed altri artisti

folk si erano esibiti nel programma di Sullivan; nel marzo del 1963

Sullivan aveva ospitato il popolare Chad Mitchell Trio. Per Dylan, un

cantante di attualità, suonare all'Ed Sullivan Show significava avere una

grande esposizione. Egli scelse per il suo numero la satirica "Talkin'

John Birch Society Blues" (Per quelli troppo giovani per ricordare: la

John Birch Society, che esiste ancora oggi, era nota per essere un gruppo

politico di estrema destra che vedeva cospirazioni comuniste dappertutto.

Il Mitchell Trio aveva proposto una canzone dal titolo "The John Birch

Society" nel 1962.)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dopo aver ascoltato la prova di Dylan appena prima della messa in onda del

programma, uno degli esecutivi della CBS, non tenendo in conto le

obiezioni di Sullivan, ordinò a Dylan di cantare qualcosa di meno

controverso. A differenza di Presley, Dylan non accettò di essere

censurato e si rifiutò di partecipare al programma. La voce della sua

mancata partecipazione allo show per questioni di principio fece brillare

la reputazione di Dylan tra i suoi fans, vecchi e giovani. Non sapevamo in

realtà che la canzone era stata già esclusa insieme ad altre tre dalla

versione originale dell'album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan.

Dylan incluse il numero bandito all'Ed Sullivan Show, nel programma del

suo concerto di Halloween del 1964, presentandolo, con un misto di sfida e

di umorismo, come "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues" - un titolo che ora

sembrava sintetizzare il pavido e generalizzato comportamento dei media

così come quello degli estremisti di destra che in quel momento stavano

suonando la marcia trionfale per il loro favorito, il Senatore Goldwater.

Fu un momento di brivido per noi che eravamo tra il pubblico, ascoltare

quel che la CBS aveva proibito alla nazione di ascoltare, mentre

esultavamo nella nostra rettitudine politica contro le forze della paura e

della lista nera (3).

"Who Killed Davey Moore?", l'altra antica canzone politica, parlava della

morte di un giovane pugile dei pesi piuma il quale, dopo aver perso il

titolo dopo un incontro con Sugar Ramos nel 1963, era entrato in coma ed

era morto. L'incidente aveva scatenato un dibattito a proposito della

possibilità di bandire la boxe negli Stati Uniti. L'episodio aveva anche

ispirato il cantautore politico (e rivale di Dylan) Phil Ochs il quale

aveva composto una lunga canzone narrativa, descrivendo nei dettagli i

pugni che volavano ed il sudore che trasudava nel ring e gli "avvoltoi in

caccia di denaro" ed i fans desiderosi di sangue. L'approccio musicale di

Dylan all'episodio fu allo stesso tempo più semplice - una rielaborazione

dell'antica "Who Killed Cock Robin?" - e più complessa, indicando le molte

persone che rifiutavano di assumersi la responsabilità per la morte di

Moore recitando le proprie deboli scuse.

Nel nastro del concerto, la reazione del pubblico appare evidente. Appena

Dylan canta "Who killed..." iniziano gli applausi. Sebbene Dylan non

avesse mai registrato la canzone, l'aveva eseguita in concerto durante il

suo show alla Town Hall, nell'aprile del 1963, meno di tre settimane dopo

che Davey Moore era morto. Erano i tempi in cui un folksinger, o almeno

questo folksinger, poteva avere una canzone che circolava dappertutto

senza nemmeno averla mai incisa su disco.

Un'altra risposta del pubblico a "Davey Moore" risulta chiara sul nastro

quando Dylan canta il verso che parla del fatto che la boxe non è più

permessa nella Cuba di Fidel Castro. Se si ascolta attentamente si può

sentire un applauso che inizia a diffondersi nella sala a sottolineare il

verso. Forse qualcuno della vecchia guardia di Sing Out! era tra il

pubblico - momentaneamente, ma solo momentaneamente, incoraggiato.

Certamente c'erano spettatori più giovani quella sera e che ancora

volevano continuare a vedere in Dylan il cantore della Rivoluzione.

Ad ogni modo Dylan non voleva essere prevedibile su niente, così persino

la sua esibizione di "Davey Moore" trascinò in altre direzioni. "Questa è

una canzone che parla di un pugile", disse prima di inizare a cantare.

"Non ha niente a che vedere con la boxe. E' solo una canzone che parla di

un pugile, davvero. E, uh, in realtà non ha nemmeno niente a che fare con

un pugile. Non ha niente a che fare con niente. Ho solo messo insieme

tutte queste parole. Questo è tutto." La presentazione irriverente tolse

solennità al brano, laddove la gente voleva e si aspettava solennità.

(Altri invece evidentemente non si aspettavano solennità e lo fecero

capire con la loro estemporanea scherzosa risposta al cantante). La risata

di Dylan a metà della sua presentazione sembrò dimostrare anche che egli

era un po' alterato. Forse che Dylan era brillo per aver bevuto del

Beaujolais - tutti sapevamo che Dylan beveva beaujolais - o forse aveva

addirittura fumato erba? Ma forse era alterato in una maniera differente,

forse aveva le vertigini a causa del posto e del pubblico e per la gioia

di essere ritornato nella sua città natale adottiva dopo settimane

trascorse a suonare nel circuito dei college. Non ha importanza: il suo

tono un po' brillo ed a volte gioioso era contagioso, e non aveva niente a

che fare con il tenere sermoni.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Aveva qualcosa a che fare con il sesso. Nessuno tra il pubblico aveva

ancora sentito "If you gotta go go now (Or else you gotta stay all night)"

ed il suo sottile, oltremodo allegro resoconto di una seduzione

ora-o-mai-più mandò tutti fuori di testa.

Eseguita dopo "Gates of Eden", fu una sorta di pausa comica, ma una pausa

comica hip. Nella canzone, il cantante sa molto bene che l'oggetto del suo

interesse non è vergine. Il sesso casuale non è più un tabù; la

repressione che circondava questa parte della vita era sparita. Quello che

Presley aveva fatto con il suo bacino, Dylan lo stava facendo con le sue

parole - discrete, informali e comiche, alimentavano la cospirazione

giovanile dei figli e delle figlie che erano (o volevano essere) "beyond

their parents' command" (4)

A volte il pubblico conosceva le parole di Dylan meglio di quanto egli

stesso le conoscesse. Verso la fine della prima metà dello show, Dylan

strimpellò la sua chitarra ma dimenticò completamente il verso iniziale

della canzone successiva. Come se si stesse esibendo al Gaslight giù nel

Greenwich Village e non alla Philarmonic Hall, Dylan chiese al pubblico di

aiutarlo, e così avvenne. Sul nastro, due voci, indubitabilmente due voci

di New York, si elevano al di sopra delle altre, una subito dopo l'altra,

con il suggerimento: "I can't understand...". La canzone, "I don't believe

you (She acts like we never have met)" era apparsa sull'album Another Side

meno di tre mesi prima, ma i suoi fans la conoscevano altrettanto bene che

"Pretty Peggy-O" (forse alla maggioranza del pubblico era persino più

familiare che non "Pretty Peggy-O.")

Dylan, un maestro del tempo, non perse un colpo, riprese il verso e

continuò la canzone alla perfezione.

Nel corso di questi intermezzi divertenti, Dylan presentò i suoi nuovi

capolavori, "Gates of Eden" e "It's all right ma (I'm only bleeding)",

chiamando quest'ultima "It's all right ma, it's life and life only."

Queste canzoni sono diventate nelle decadi successive delle vere e proprie

icone musicali, le loro immagini contorte sono diventate talmente parte

del subconscio di una generazione che è difficile ricordarsi come

sembrarono quando furono sentite per la prima volta in un concerto. Dylan

sapeva che erano speciali e che sarebbero volate via dalla mente degli

spettatori la prima volta. Giocò persino su questa cosa sul palco (sul

nastro la risata di uno spettatore saluta l'annuncio da parte di Dylan di

"It's all right ma" come se la canzone fosse una presa in giro; e Dylan

cinguetta "Sì, è una canzone molto divertente.")

Durante queste esibizioni, il pubblico era assolutamente silenzioso,

cercando di cogliere le parole che Dylan pronunciava, ma alla fine fu

travolto dall'intensità delle liriche e della musica di Dylan anche se

questi sbagliò un verso. Non avremmo avuto la possibilità di riascoltare

quelle canzoni per altri cinque mesi, quando furono pubblicate su Bringing

it all back home - e persino allora ci vollero ripetuti ascolti per capire

ogni singolo verso. All'epoca sembrò che fosse poesia, poesia epica

(entrambe le canzoni duravano tanto da sembrare poemi Omerici) e provarono

che Bob Dylan ci stava portando in nuovi posti, in territori sconosciuti

ma molto attraenti.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

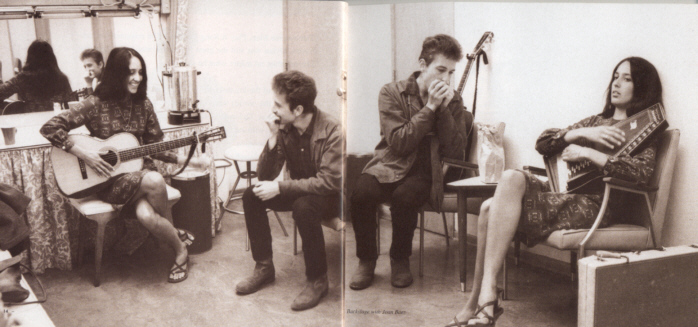

La seconda metà dello show ci riportò su un terreno familiare: canzoni

tratte da "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan" e da "The times they are

a-changin'", e tre duetti con Joan Baez. (la Baez cantò anche "Silver

Dagger" accompagnata da Dylan all'armonica).

Dylan e la Baez - il re e la regina del movimento folk, che tutti sapevano

essere amanti - avevano cantato insieme per oltre un anno. La Baez aveva

portato con sè Dylan sul palcoscenico durante molti dei propri concerti,

incluso quello a Forest Hills in agosto, e adesso Dylan stava

ricambiandole il favore. Dylan e la Baez cantarono di desiderio, di

desiderio respinto, e di Storia Americana, il loro armonizzare in alcuni

momenti fu ispido, ma con una tale disinvoltura tra di loro che addolcì

ulteriormente il canto. E' stato detto molto a proposito del rapporto tra

Dylan e la Baez in questi anni, a volte in maniera non lusinghiera per

l'uno o per l'altra. Proprio come la Camelot dei Kennedy avrebbe avuto i

suoi ridimensionamenti, così il magico regno che noi inventavamo intorno a

Bob Dylan ed a Joan Baez sarebbe crollato. Comunque quasi dimenticati - ma

catturati sul nastro della Philarmonic Hall persino nelle esibizioni

farsesche di quella sera - sono stati i ricchi frutti della loro

collaborazione canora. Joan è sempre sembrata, sul palcoscenico, la più

fervida, e rispettosa, anche troppo, della presenza del Ragazzo Genio; e

Bob alle volte avrebbe gentilmente preso in giro quel fervore, proprio

come fa in questo disco tra una canzone e l'altra. Ma quando cantavano

insieme, erano davvero una coppia; la ruvidezza nasale di lui si mescolava

in maniera meravigliosa con la morbida coloritura di lei, e le loro linee

armoniche aggiungevano profondità alle melodie, il piacere puro che

entrambi provavano stando l'uno in compagnia dell'altra traspare dalle

loro voci.

Ascoltando il nastro, il mio duetto preferito dallo show della Philarmonic

Hall è "Mama you been on my mind" in cui la Baez canta "Daddy" invece di

"Mama". Poi, durante uno dei brevi interludi strumentali, la Baez

inserisce "shooka-shooka-shooka-shook-shooka" - quello che nessuno si

sarebbe aspettato dalla regina del folk, qualcosa di molto più pop o

persino rock 'n' roll che non la musica folk. Forse che anche Joan stava

ascoltando i Beatles? Non mi ricordo di aver sentito ciò all'epoca ma ora

lo si potrebbe interpretare come un altro piccolo presagio delle cose a

venire.

Dylan chiuse lo show da solo con il suo bis. Il cantante ed il pubblico

erano ora come una cosa sola; richieste gridate riempirono l'aria, ci fu

chi chiese che Dylan cantasse "Chimes of freedom", chiesero di tutto,

persino "Mary had a little lamb". "Dio, ho registrato anche quella?",

scherzò Dylan crogiolandosi nel baccano. "E' forse una canzone di

protesta?" Egli scelse "All I really want to do," un'altra delle canzoni

di "Another Side" preferite dal pubblico. Era forse un dolce, segreto

addio a Joan Baez? Era un gentile addio a tutti noi, o a quelli di noi che

volevano fare di Dylan, a nostro modo, qualcosa di più di quanto egli

poteva effettivamente essere?

Durante la prima parte del concerto, dopo aver cantato "Gates of Eden",

Dylan parlò per un po' a proposito del fatto che la canzone non avrebbe

dovuto far paura ad alcuno, che si trattava soltanto di Halloween e che

lui indossava la sua maschera di Bob Dylan. "Sono mascherato!" scherzò,

prolungando la seconda parola in una risata. Lo scherzo era serio. Bob

Dylan, nato Zimmerman, aveva coltivato brillantemente la propria fama, ma

egli in realtà era un entertainer, un uomo dietro una maschera, un grande

entertainer forse, ma di base semplicemente quello - qualcuno che metteva

insieme parole, per quanto esse fossero sbalorditive. L'onere di essere

qualcosa d'altro - un guru, un teorico politico, "la voce di una

generazione", come egli in maniera faceta aveva dichiarato nel corso di

un'intervista pochi anni prima - era davvero troppo da chiedere a

chiunque. Noi tra il pubblico gli chiedevamo di essere tutto quello ed

anche di più, ma Dylan si stava liberando dal giogo. Tutto quello che

davvero egli voleva fare era essere un amico, se possibile, ed un artista

che scriveva e cantava le proprie canzoni. Egli ci stava dicendo proprio

quello, anche se noi non volevamo credergli, e non lo lasciavamo essere

così. Volevamo di più.

"Don't follow leaders

Watch the parking meters"

- Bob Dylan, 1965.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Meno di tre mesi dopo il concerto della Philarmonic Hall, Bob Dylan era

nello studio A della Columbia Records a Manhattan per la seconda sessione

di registrazione di "Bringing it all back home" - ed egli portò con sè due

chitarristi, due bassisti, un batterista ed un pianista. Una delle prime

canzoni che Bob ed i musicisti registrarono fu "Subterranean homesick

blues", un numero rock alla Chuck Berry, più recitato che cantato, un

brano che parlava di esche, di trappole, di caos, e di "non seguire i

leaders". Quella primavera, Dylan sarebbe andato in tour in Inghilterra e

sarebbe ritornato alla sua scaletta acustica, ma il film realizzato

durante quel tour, "Don't look back", lo mostra palesemente stufo di quel

materiale. Il nuovo album semi-elettrico apparve a marzo; in estate "Like

a rolling stone" fu trasmessa dalle radio; ed alla fine di luglio ci fu il

famoso set completamente elettrico a Newport che scatenò una guerra civile

tra i fans di Dylan. Egli non era più da solo con la sua chitarra e con la

sua armonica. Il simpatico joker adesso indossava sinistri stivali di

pelle nera ed una giacca lucida a fare il paio. E non c'era più Joan Baez.

Un po' del vecchio Dylan riapparve quando egli fu quasi costretto a

ritornare sul palco per suonare alcune delle sue vecchie canzoni

acustiche. "Qualcuno ha un'armonica in sol? Un'armonica in sol, qualcuno

ce l'ha?", chiese al pubblico. Ed armoniche in sol piovvero dalla folla

sul palcoscenico. Ma ora il congedo era inequivocabile, quando Dylan cantò

alla gente una sorta di serenata con "It's all over now, baby blue",

accanto a "Mr. Tambourine Man".

Un anno dopo - con la guerra del Viet Nam che divideva il paese, ghetti

urbani circondati da incendi dolosi e da tumulti - Dylan sarebbe stato

coinvolto nel suo famoso incidente motociclistico, concludendo un periodo

sfrenato durante il quale aveva spinto la sua capacità di innovazione ai

limiti estremi con "Blonde on blonde" e con i suoi stupefacenti concerti

con gli Hawks - non ultimo lo show in cui gli gridarono "Judas" a

Manchester, Inghilterra, ricatturato di recente su "Live 1966".

"Live 1964" ci restituisce un Bob Dylan al vertice di quel tumulto. Ci

riporta indietro ad un tempo tra i suoi set nei club di downtown ed i

grandi tour nelle arene rock degli anni '70 e degli anni successivi. Ci

restituisce un'epoca ormai passata di intimità tra artista e pubblico, e

gli ultimi barlumi della autoconsapevole vita bohemienne di New York prima

che essa fosse annacquata e massificata. Ci restituisce un momento di

Dylan appena prima che qualcosa che Pete Hammill (nelle note introduttive

dell'album "Blood on the tracks") definì "il flagello" infettasse così

tante speranze, e distruggesse un'America di epoche precedenti, quella

cantata da Woody Guthrie e descritta in prosa da Jack Kerouac - e

naturalmente dallo stesso Dylan. Ma soprattutto ci restituisce un grande

concerto di un artista che era al culmine della propria potenza - e che

avrebbe raggiunto in seguito molte altre vette.

- Sean Wilentz, Princeton, Dicembre 2003.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NOTE:

(1) In inglese: "perfumed gull", "curfewed gal"

(2) It's all right ma (I'm only bleeding)

(3) Lista dei personaggi del mondo dello spettacolo, del cinema etc.

sospettati di simpatie comuniste e banditi dai programmi televisivi etc.

(4) "Al di là dei comandi dei loro genitori", la citazione è da The Times

They Are A-Changin'.

°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°

LINER NOTES BY SEAN

WILENTZ FROM "THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 6: CONCERT AT PHILARMONIC HALL"

On Halloween night, 1964, a twenty-three-year old Bob Dylan spellbound an

adoring audience at Philharmonic Hall in New York. Relaxed and

high-spirited, he sang seventeen songs, three of them with his guest Joan

Baez, plus one encore. Many of the songs, although less than two years

old, were so familiar that the crowd knew every word. Others were brand

new and baffling. Dylan played his heart out on these new compositions, as

he did on the older ones, but only after an introductory turn as the

mischievous tease.

"This is called 'A Sacrilegious Lullaby in D minor,'" he announced, before

beginning the second public performance ever of "Gates of Eden."

He was the cynosure of hip, when hipness still wore pressed slacks and

light-brown suede boots (as I remember he did that night). Yet hipness was

transforming right on stage. Dylan had already moved on, well beyond the

most knowing New Yorkers in the hall, and he was singing about what he was

finding. The show was in part a summation of past work and in part a

summons to an explosion for which none of us, not even he, was fully

prepared.

"Because Dickens and Dostoevsky and Woody Guthrie were telling their

stories much better than I ever could, I decided to stick to my own mind"

— Bob Dylan, 1963.

The world seemed increasingly out of joint during the weeks before the

concert. The trauma of John F. Kennedy's assassination less than a year

earlier had barely abated. Over the summer, the murders in Mississippi of

the civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael

Schwerner had created traumas anew. President Lyndon Johnson managed to

push a Civil Rights Bill through the Congress in July 1964; by early

autumn, it seemed as if he would trounce the arch-conservative Barry

Goldwater in the coming election. But in August, Johnson received a

congressional blank check to escalate American involvement in the Vietnam

conflict. On a single day in mid-October, Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev

was overthrown and Communist China exploded its first atomic bomb. A

hopeful phase of the decade was quickly winding down, and a scarier phase

loomed.

Dylan's style and his art were changing too, with an accelerating and

bewildering swiftness befitting the times. In December 1963, Dylan had

offended a leftist New York audience by accepting a free-speech award with

some atrociously-wrought, off-the-cuff remarks about hypocrisy, youthful

alienation, and how he saw a bit of himself in Lee Harvey Oswald.

Proclaimed by the leftists as the latest incarnation of Woody Guthrie, a

new political cult hero, Dylan had seemed uncomfortable, pleased to be

honored but unwilling to accept the heavy mantle that all of these old

people, for their own reasons, wanted to thrust upon him; and so,

ambivalent and easily misunderstood, he thrust it back. The singer

offended even more people the following summer with the release of Another

Side of Bob Dylan—an album devoid of the fixed moral standpoint in his

earlier protest self, and containing instead songs of personal freedom,

whimsy, and wounded love. In the wake of the Beatles' take-over of

American top-40 radio, some members of the older Popular Front folk

establishment shook their heads in dismay at what was becoming of their

new Woody Guthrie. One folk commissar, writing in the respected Sing Out!

Magazine, would sneer at Dylan as a political sell-out and try to force

him into line, warning him not to turn into "a different Bob Dylan than

the one we knew." Little did he know that Dylan was not simply becoming

different; he was also listening to the Beatles.

Dylan has since recalled how much the criticism of Another Side stung, and

how proud he was when, out of the blue, Johnny Cash wrote a stern letter

to Sing Out! in his defense. (To this day, Dylan says, he's held on to his

copy of the magazine with Cash's letter in it.) But at the time, he

outwardly betrayed no injured feelings and kept on writing and performing

in his new vein. The great majority of his fans, especially his younger

fans, seemed to approve. At the Newport Folk Festival in July, two weeks

before Another Side appeared, he stuck almost entirely to playing new

material, along with one as-yet-unrecorded song that he introduced to an

afternoon workshop session as "Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, Play a Song For

Me." The response was rapturous. Dylan was still the great folk-music

star, a phenomenon like no other, no matter what he sang.

For most of the loyalists, the shifts in Dylan's style (unlike in the rest

of the world) were not disturbing. Amid the English Rock Invasion, Dylan

still stood on stage alone, singing and playing with nothing more than his

guitar and his rack-clamped harmonica. When he wasn't alone, he sang, at

Newport and elsewhere, with Joan Baez, whose presence and endorsement of

Dylan's new songs eased our own transition. Dylan's politics actually

hadn't disappeared, but had only become less preachy and much funnier, as

in the joke-saga, "Motorpsycho Nitemare," on Another Side. Dylan had

always sung intensely personal songs. His most powerful earlier political

material often involved human-sized stories, like "The Lonesome Death of

Hattie Carroll." And amid the disorientation of late 1963 and 1964, who

was to say that a turn to introspection was out of place?

The Beatles, with their odd chords and joyful harmonies, were great, but

what was "She Loves You" compared to the long-stemmed word imagery in

"Chimes of Freedom"? Who else but Dylan would be brainy enough and with-it

enough to toss off allusions in his songs to Fellini films and Cassius

Clay? To his fans, he may have been evolving, but so were we; and the Bob

Dylan we now heard and saw seemed basically the same as the Bob Dylan we

knew, only better. Looking back on it, we probably had no more of a clue

about where he was headed than the Sing Out! writer did. But at the time,

for those of us who wanted to be as close to the blade's edge of the

avant-garde as possible—or as close as we dared—Dylan could do no wrong.

"I don't want to fake you out,

Take or shake or forsake you out,

I ain't lookin' for you to feel like me,

See like me or be like me" — Bob Dylan, 1964.

That Dylan's management booked Philharmonic Hall for its star's biggest

show of the year was testimony to his allure. Opened only two years

earlier as the first showcase of the neighborhood-killer Robert Moses' new

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Philharmonic Hall (now Avery

Fisher Hall) was, with its imperial grandeur and bad acoustics, the most

prestigious auditorium in Manhattan—or for that matter in the entire

country. Within two years of releasing his first album, Dylan's New York

venues had shot ever upward in cachet (and further uptown), from Town Hall

to Carnegie Hall and now to the sparkling new home of Leonard Bernstein

and the New York Philharmonic. When the expectant audience streamed out of

the grungy old mosaic-tiled IRT subway stop at 66th Street, and then

crammed into the cavernous gilded theater, it must have looked to the

uptowners (and the ushers) like a bizarre invasion of the hipster beatnik

young.

As if to make sure that we knew our place, a man appeared on stage at show

time to warn us that there would be no picture-taking or smoking permitted

in the house. Then, like Bernstein striding to his podium, Dylan walked

out of the wings, no announcement necessary, a fanfare of applause

proclaiming who he was. He started the concert, as he normally did, with

"The Times They Are A-Changin.'" Here we all were, the self-consciously

sensitive and discerning, settling in—at a Dylan show like any other,

whatever the plush surroundings. Two hours later, we would leave the

premises and head back underground to the IRT, exhilarated, entertained,

and ratified, but also confused about the snatches of lines we'd gleaned

from the strange new songs. What was that weird lullaby in D minor? What

in God's name is a perfumed gull (or did he sing "curfewed gal")? Had

Dylan really written a ballad based on Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon?

The melodies were strong; and the playing on the "darkness" song had been

ominous and overpowering, but it had all moved so fast that comprehension

was impossible. It had turned into a Dylan show unlike any we'd ever heard

or heard about.

Thanks to an excellent tape, presented here for the first time in its

entirety, it is now possible to appreciate what happened that night — not

just in what Dylan sang, but in what he said, and in the amazing audible

rapport he had with his audience.

The show was divided in two, with a fifteen-minute intermission. The first

half was for innovation as well as for some glances at where Dylan had

already been. Two of the most pointedly political older songs,

interestingly, had never been issued on record, but the audience knew them

anyway, and responded enthusiastically.

Back in May 1963, Dylan had been booked on the Ed Sullivan Show, the

premier Sunday night television variety program, where Elvis Presley had

made three breakthrough appearances seven years earlier and had agreed, on

the final show, to be shown performing only from the waist up. The

downtown Irish traditional folk group the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem

had appeared on Sullivan twice, vastly enlarging their following. (They

played Philharmonic Hall a year before Dylan did.) The Limelighters, the

Lettermen, the Belafonte Folk Singers, and other folk acts had also

performed on the Sullivan program; in March 1963, Sullivan hosted the

popular Chad Mitchell Trio. For Dylan, an edgy topical singer, playing the

Ed Sullivan Show would mean huge exposure. He chose as his number the

satirical " Talkin' John Birch Society Blues."

(For those too young to remember: the John Birch Society, which still

exists, was notorious as a hard-right political group that saw Communist

conspiracies everywhere. The Mitchell Trio had enjoyed a minor hit with

its own mocking song, "The John Birch Society," in 1962.)

Upon hearing Dylan's selection at the rehearsal, just before air time, a

CBS executive turned cold and, over Sullivan's objections, ordered him to

sing something less controversial. Unlike Presley, Dylan would not be

censored and he refused to appear. Word of his principled walk-out

burnished Dylan's reputation among his established fans, old and young.

Little did we know that the song had also been dropped, along with three

others, from the original version of Freewheelin.'

Dylan included the banned number on his 1964 Halloween program,

introducing it, with a mixture of defiance and good humor, as "Talkin'

John Birch Paranoid Blues"—a title that now seemed to cover the craven

mainstream media as well as the right-wing extremists who were currently

thumping their tubs for their favorite, Senator Goldwater. It was a

thrilling moment for us in the audience, getting to hear what CBS had

forbidden the nation to hear while also exulting in our own political

righteousness against the forces of fear and blacklisting.

"Who Killed Davey Moore?," the other older political song, was about the

death of a young featherweight boxer who, after losing a title bout to

Sugar Ramos in 1963, fell into a coma and died. The incident sparked

public debate about whether boxing should be banned in the United States.

It also inspired the political songwriter (and Dylan's rival) Phil Ochs to

compose a narrative song, describing in detail the flying fists and

pouring sweat inside the ring and the "money-chasing vultures" and

blood-lusting fans outside it. Dylan's musical take on the episode was at

once simpler—a reworking of the ancient "Who Killed Cock Robin?" theme

—and more complex, pointing out the many people who bore responsibility

for Moore's death and reciting their lame excuses.

On the concert tape, the audience's instant adulatory reaction stands out

most of all. As soon as Dylan sings "Who killed…," the cheering starts.

Although Dylan had not recorded the song, he had been performing it in

concert as early as his Town Hall show in April 1963, less than three

weeks after Davey Moore died. It was a time, one now remembers, when a

folk singer, at least this one, could have a song of his achieve wide

currency without even putting it on a record, let alone getting it played

on the radio.

Another response to "Davey Moore" also stands out on the tape, when Dylan

comes to the line about boxing no longer being permitted in Fidel Castro's

Cuba. Listen closely, and you will hear some scattered applause approve

the sentiment. Maybe some of the Sing Out! old guard was in the audience—

momentarily, but just momentarily, encouraged. Certainly there were

younger people there, the red-diaper babies and other politicals, who

still wanted to hold onto Dylan as the troubadour of the Revolution.

Dylan, however, would not be type-cast as anything, and even his rendering

of "Davey Moore" tugged in other directions. "This is a song about a

boxer," he said before he sang it. "It's got nothing to do with boxing,

it's just a song about a boxer really. And, uh, it's not even having to do

with a boxer, really. It's got nothing to do with nothing. But I fit all

these words together, that's all." The irreverent introduction undercut

solemnity, even though some people wanted and expected solemnity. (Others

in the audience did not, and made that clear in their impromptu badinage

with the singer.) Dylan's laughter in the middle of his introduction even

sounded a little intoxicated. Was he aglow from drinking Beaujolais—we all

knew Dylan drank Beaujolais—or maybe, even cooler, had Dylan been smoking

pot? Perhaps he was intoxicated in a different way, giddy from the hall

and the affectionate crowd and the joy of being back in his adopted

hometown after weeks of playing the college circuit. No matter: his

mellow, at times merry mood was infectious, and it had nothing to do with

sermonizing.

It did have something to do with sex. Nobody in the audience had yet heard

"If You Gotta Go, Go Now;" and its sly, rollicking account of an

it's-now-or-never seduction sent everybody into stitches. Coming after

"Gates of Eden," it was a bit of comic relief, but hip comic relief. In

the song, the singer knows very well that the object of his affections is

no virgin. Casual sex is no longer taboo; the repression surrounding this

part of life has lifted. What Presley had done with his pelvis, Dylan was

doing with his words—coy, conversational, and comical, feeding the youth

conspiracy of sons and daughters who were (or wanted to be) beyond their

parents' command.

Sometimes, the audience knew Dylan's words better than he did. Nearing the

end of the show's first half, Dylan strummed his guitar but completely

forgot the next song's opening line. As if he were performing at the

Gaslight down in Greenwich Village and not in Philharmonic Hall, Dylan

asked the audience to help him out, and it did. On the tape, two voices,

unmistakably New York voices, carry above all the others, one rapidly

following the other with the cue: "I can't understand...." The song, "I

Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)" had appeared on

Another Side less than three months earlier, but his fans knew it so well

that it might have been "Pretty Peggy-O." (It may have even have been more

familiar to most of the audience than "Pretty Peggy-O.") Dylan, a master

of timing, did not miss a beat, picked up the line, and then sang the song

flawlessly.

Between these funny moments, Dylan introduced his new masterpieces, "Gates

of Eden" and "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)," calling the latter,

"It's All Right Ma, It's Life and Life Only." These songs have become such

iconic pieces over the intervening decades, their twisting images so much

a part of a generation's sub-conscious, that it is difficult to recall

what they sounded like when heard for the first time, and in concert.

Dylan knew that they were special, and that they would fly over his

listeners' heads the first time around. He even joked about that on stage.

(On the tape, some laughter greets Dylan announcement of "It's All Right

Ma," as if the song title is a put-on; and he pipes up, "Yes, it's a very

funny song.") During these performances, the audience was utterly silent,

trying at first to catch the words, but finally bowled over by the

intensity of both the lyrics and Dylan's playing, even when he muffed a

line. We would not get the chance to figure the songs out for another five

months, when they appeared on Bringing It All Back Home—and even then it

would take repeated listenings for any of it to make sense. At the time,

it just sounded like demanding poetry, epic poetry (each went on for what

seemed like Homeric length), proving once again that Bob Dylan was leading

us into new places, the whereabouts unknown but deeply tempting.

The evening's second half brought us back to familiar ground: songs from

Freewheelin' and The Times They Are A-Changin', and three duets with Joan

Baez. (Baez also sang "Silver Dagger," accompanied by Dylan on the

harmonica.) Dylan and Baez—the king and queen of the folk movement, known

to be lovers — had been performing together off and on for well over a

year. Baez had brought Dylan to the stage during several of her concerts,

including one at Forest Hills in August, and now Dylan was returning the

compliment. They sang of desire, rejected desire, and American history,

their harmonizing ragged in places, but with an ease between them that

further mellowed the mood even as it upped the star wattage on stage.

Plenty has been made since about Dylan and Baez's relationship in these

years, some of it unflattering to one or the other or both of them. Much

as the Kennedys' Camelot would have its debunkers, so the magical kingdom

we conjured up around Bob Dylan and Joan Baez would come crashing down.

Nearly forgotten, however — but captured on the Philharmonic tape, even in

that night's laid-back, knockabout performances — have been the rich

fruits of their singing collaborations. Joan always seemed, on stage, the

earnest, worshipful one, overly so, in the presence of the Boy Genius; and

Bob would sometimes lightly mock that earnestness, as he does between

songs here. But when singing together, they were quite a pair, his nasal

harshness mingling wonderfully with her silken coloratura, their harmony

lines adding depth to the melodies, their sheer pleasure in each other's

company showing in their voices.

Listening to the tape, my favorite duet from the Philharmonic show is

"Mama, You've Been On My Mind." Baez sings "Daddy" instead of "Mama."

Then, during one of the brief instrumental interludes, she interjects a

"shooka-shooka-shooka, shooka-shooka"—nothing one would expect from the

Folk Queen, something more pop or even rock 'n' roll than folk music. Was

our Joan listening to the Beatles, too? I don't recall hearing this at the

time, but now it sounds like another little portent of things to come.

Dylan closed, solo, with his encore. The singer and audience were by now

as one; shouted requests filled the air, for "Chimes of Freedom," for

anything, even for "Mary Had a Little Lamb." "God, did I record that?"

Dylan joked back, basking in the revelry. "Is that a protest song?" He

chose "All I Really Want to Do," another crowd-pleaser from Another Side.

Was this a secret sweet envoi to Joan Baez? Was it a gentle envoi to us,

or the part of us that wanted to make of Dylan, in our own way, something

more than he could possibly be?

During the first half of the concert, after singing "Gates of Eden," Dylan

got into a little riff about how the song shouldn't scare anybody, that it

was only Halloween, and that he had his Bob Dylan mask on. "I'm

masquerading!" he joked, elongating the second word into a laugh. The joke

was serious. Bob Dylan, né Zimmerman, brilliantly cultivated his

celebrity, but he was really an artist and entertainer, a man behind a

mask, a great entertainer, maybe, but basically just that—someone who

threw words together, astounding as they were. The burden of being

something else — a guru, a political theorist, "the voice of a

generation," as he facetiously put it in an interview a few years ago —

was too much to ask of anyone. We in the audience were asking him to be

all of that and more, but Dylan was slipping the yoke. All he really

wanted to do was to be a friend, if possible, and an artist writing and

singing his songs. He was telling us so, but we didn't want to believe it,

and wouldn't let him leave it at that. We wanted more.

"Don't follow leaders,

Watch the parking meters" — Bob Dylan, 1965.

Less than three months after the Philharmonic Hall concert, Bob Dylan

showed up at Columbia Records' Studio A in Manhattan for the second

session of recording Bringing It All Back Home — and he brought with him

three guitarists, two bassists, a drummer and a piano player. One of the

first songs they recorded was "Subterranean Homesick Blues," a Chuck

Berryish rock number, less sung than recited, about lures, snares, chaos,

and not following leaders. That spring, Dylan would tour England and

return to his acoustic playlist, but the film made of that tour, Don't

Look Back, shows him obviously bored with the material. The new

half-electric album appeared in March; by mid-summer, "Like a Rolling

Stone" was all over the radio; and in late July came the famous

all-electric set at Newport that sparked a civil war among Dylan's fans.

He was no longer standing alone with his guitar and harmonica. The

pleasant joker now wore sinister black leather boots and a shiny matching

jacket. No more Joan Baez. A bit of the old rapport reappeared when Dylan

was coaxed back onstage to play some of his acoustic material. "Does

anybody have an E harmonica, an E harmonica, anybody?" he asked — and E

harmonicas came raining out from the crowd and thumped onstage. But now

the envoi was unmistakable, as Dylan serenaded the folkies with "It's All

Over Now, Baby Blue," as well as "Mr. Tambourine Man." A year after that —

with the Vietnam war tearing the country apart, urban ghettos beset by

arson and riots, and conservative backlash coming on strong — Dylan would

suffer his famous motorcycle crack-up, concluding the wild period when he

pushed his innovations to the limit with Blonde On Blonde and with his

astonishing concerts with the Hawks, not least the "Judas" show in

Manchester, England, re-captured now on Live 1966.

Live 1964 brings back a Bob Dylan on the cusp of that turmoil. It brings

back a time between his scuffling sets at the downtown clubs and his

arena-rock tours of the 1970s and after. It brings back a long gone era of

intimacy between performer and audience, and the last strains of a

self-aware New York bohemia before bohemia became diluted and mass

marketed. It brings back a Dylan moment just before something that Pete

Hamill (on the liner notes to Blood On the Tracks) called "the plague"

infected so many hopes, and destroyed an older America sung of by Guthrie

and, in prose, by Jack Kerouac—and by Dylan as well, who somehow survived.

Above all, it brings back a great concert by an artist performing at the

peak of his powers—one who would climb many more peaks to come.

—Sean Wilentz, Princeton, December 2003.